|

Back in the 1957, four-string specialist Paul Chambers put out an LP called Bass On Top. Now while bassists Damon Smith and Joscha Oetz are definite team players on these CDs, that title could be used to describe the state of the bass -- hm, another potential title -- in 21st century California.

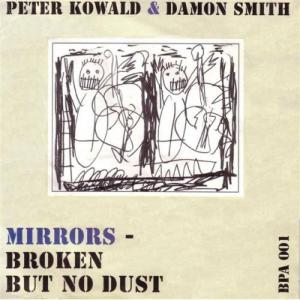

Smith, a native of Oakland, Calif., has already recorded a series of fine CDs, encompassing a duo with his bass mentor Peter Kowald, and in trios with different saxophonists, drummers and keyboardists. DESERT SWEETS is a souvenir of a visit to the Bay area by Swedish saxophonist/flautist Biggi Vinkeloe -- who recorded with Kowald in the past -- where she was matched with Smith and tuba player Mark Weaver from Albuquerque, NM. Cologne, Germany-born Oetz, moved to San Diego, CA, about 500 miles south of the Bay area, a couple of years ago. Vieles Ist Eins includes three solo bass tracks; one duet with German tenor saxophonist Andreas Wagner; one with local percussionist Greg Stuart; and five with long-time American expatriate, bassist Barre Phillips.

Bustling with interesting improvisations, the two discs illustrate three escalating trends in improvised music. For a start they -- like a high percentage of other exceptional sounds -- were created outside of so-called major American music centres like New York and Los Angles. Both feature an admixture of European and American musicians. And the two highlight non-standard instrumental combinations. This is especially apparent on Smith's disc, where in a way, Weaver's tuba functions as both a rhythm and a solo instrument. An educator, the low brassman works on-and-off with other bands featuring Smith, drummer Dave Wayne of Santa Fe, N.M. and San Diego-based multi-reedman Alan Lechusza.

During the course of the 22(!) tracks on this disc, Weaver shows off his facility in all ranges of his instrument. At times, as on tunes like "Jojoba" he produces a high-pitched ghostly sound as if he was the personification of a child's nightmare, while on other instant compositions such as "Cholla" his tone is mineshaft deep as he rumbles and reverberates in the basso region. He can even turn out falsetto cries that by rights should come from a cornet as he does on "Biting Cactus."

He's versatile as well. Take "Mesquitilla" for example. Here Weaver's phrases are both legato and staccato with his musical output moving from the very bottom of his valves to the very top of his mouthpiece, as Smith bangs his strings for a percussion effect and Vinkeloe ornaments the proceedings.

With the three often functioning as if they were interlocking parts of a single instrument, Smith is as often the percussive force as anyone else. He uses his bow to whack the strings in such a way that they become four reverberating drum skins. He can strum the strings as if he was playing a banjo, pluck them in a traditional jazz manner or create tones that sound as if he's giving them and the bass body a spring cleaning. Elsewhere, as on "Incienso," he scratch away on the strings as if he was a small animal let loose on a telephone wire, while Weaver keeps the mood buoyant by blowing nearly imperceptible tuba lines.

Northern guest Vinkeloe divided her embouchure between flute and alto saxophone. On the former she comes out with a wide, dissonant tone that's slightly sharper than that of most saxophonists'. When expressed it can take up a lot of aural space as on "Yellow Sweetclover." On the other hand, in response to the elephantine tuba rumble and low bass lines, she can put a Middle-Eastern cant to her solos, as on "Utah Juniper."

Flute finds her with a different persona, expressing the sort of gritty respiring in which Rahsaan Roland Kirk and others used to specialize. There's even a time on "Tasajillo" that she seems to be straying into repetitive Energy Music territory in contrast to Weaver's lightly articulation blasts and Smith's percussive ostinato. Overtones that can arise from both her horns are showcased on "Chili Coyote," a near-ballad which unrolls over the soundfield created by swelling low notes from Weaver and constant plucking from Smith. At slightly less than five minutes this number point out one weakness of the recital -- the extreme brevity of the tracks. With some clocking in at barely 11/2 minutes, you wish some themes and techniques had been given longer times to germinate and develop.

Tunes range throughout the time clock on Oetz's disc, with the shortest tracks bass solos. He does leave himself open to ethnic stereotyping on "M�sica Alemana," the first number which he announces as "German music." Using strings "prepared" with small round wooden sticks inserted between them, close to the bridge, he slashes the instrument and carries the piece forward with the power of an elite panzer division.

Luckily his subsequent solitary displays are less bellicose, with the more-than-seven minutes of "Konstantin" including frequent moments of silence as if he's pausing for thought. Played arco with string reverb, he sounds more than one note at a time and attaches himself more to the New music tradition than he does elsewhere.

Facing percussionist Greg Stuart on the other hand, both quickly get knee deep into EuroImprov, with the drummer utilizing what sounds like chain rattles, palm strokes on his drum heads, pealing bells and ritualistic cymbal pings, plus at one point, the suggestion of Afrocuban percussion. Oetz alternates between scraping out his melodies and concentrating his strings as bass percussion.

Recorded three years before the rest of the album, "Sipan" find the bassist plus saxophonist Wagner in an even more experimental frame of mind. Echoing tongue slaps and squeaks, that culminate in an elongated goose call, characterize the sax work so that Oetz make extensive, colorful use of those sticks between his strings.

Partnerships rather than a duels or tutorials, Oetz's five meetings with Phillips provide an object lesson in all that can be done with eight strings. At times relying on supple romantic legato lines or single bow strokes that produce a unique twanging, the results are most distinctive when each defines his own identity. On "Toqua," for instance, both slink into a pizzicato flamenco mode that after some woody reverb slides into a steady accelerating march tempo. Soon one is pressing straightahead, while the other is extending the strings away from the bridge and smashing the bow against them.

Alternately, when they're not moving in lockstep with one another on "Roronra," the strumming and picking seems to resolve itself as one creating the sound of a dobro, while the other creates what a bass guitar would play in surf music.

Song titles on both CDs couldn't be more different, with Smith & Co. honoring flowering plants and Oetz mixing German and Spanish words. Yet both discs are outstanding. Either or both should please bass fanciers, Californians and those interested in modern music.

|